An American in New York

TWO CENTS | DEC 02, 2021

An American in New York

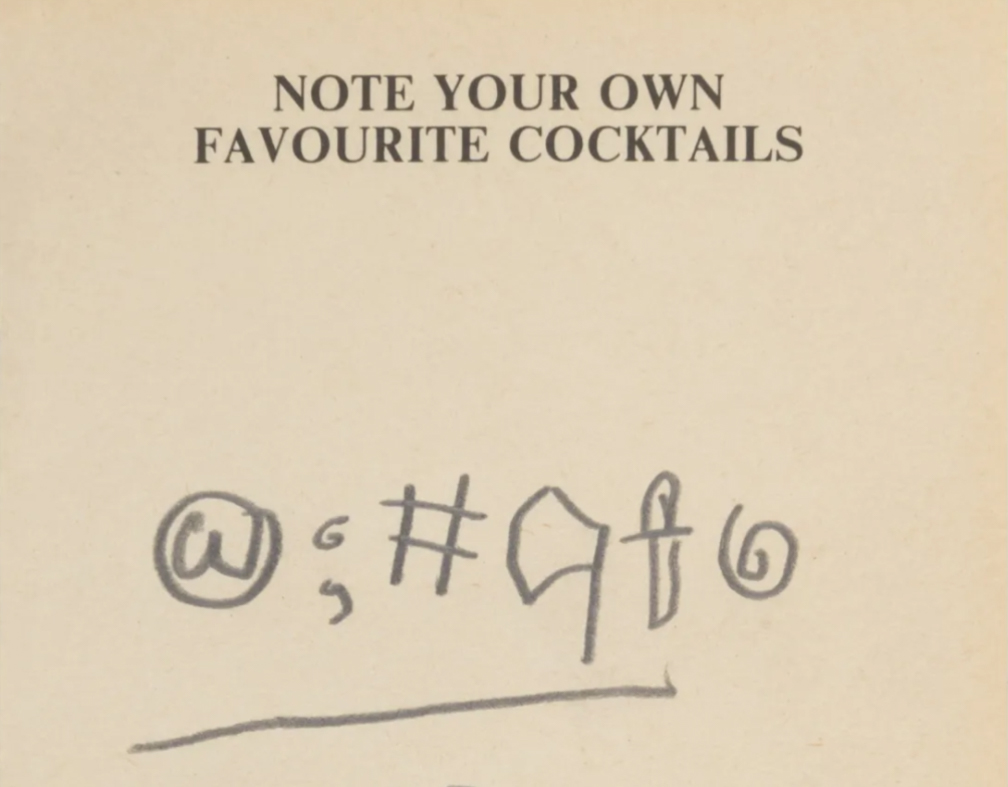

Six pages of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s drawings sit upon blank-back pages in a copy of Harry’s ABC of Mixing Cocktails. After four decades in a safe deposit box, the work is entirely new to the world.

In Los Angeles, I have no regular local spot. I moved from New York and poked around a few places I thought might become a go-to. Six months later the world shut down, effectively guillotining any chance I had of becoming an established patron anywhere. Maybe it’s me, maybe it’s the world, but I’m not sure I’ll ever again feel exactly that sense of easy comradeship. I was already pining for that New Yorker’s sense of familiarity when the story of so many other people’s go-to crossed my desk early this fall. Two go-tos, actually, thanks to a new public treasure unearthed.

The guitarist Randy Gun, a long time habitué of the downtown Manhattan music scene in the 1970’s and 80’s, recently made it known to the art world that almost forty years ago, he received an extraordinary gift. Plenty of people remember Great Jones Cafe in Noho in its original incarnation, and plenty remember that Randy had been a regular barman almost since its opening in 1983. The Jones was known for great burgers, the kind-of Cajun menu inscribed on the wall, and one of its frequent patrons and Randy’s friend, Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Jean-Michel would stop by during set up, before they were open, and sit at Randy’s bar with no one else around. By the time the doors opened at four o’clock in the afternoon, he’d be gone. He ordered margaritas, straight up, no salt, foregoing the offer of an upbrand tequila in favor of, “the ordinary house rack rot,” by Randy’s description. “The only thing special he asked for was fresh lime juice, and I would squeeze it right in front of him.”

I can only imagine the quietly recuperative hour that passed between them while Jean-Michel reset his clocks and restored his bearings for the characteristically long evening hours ahead. Anyone who has worked in service knows that those pre-public hours are sacrosanct; meditative or, sometimes, an unhinged moment of fortifying your own mental state for the impending onslaught of other people’s energy. If a bartender regularly allowed his friend to be there for a mid-afternoon tipple, it must have been one mutually respectful relationship, indeed.

In 1986, Jean-Michel came back to New York from traveling and said, “I was thinking of you on this trip, and I brought back this book for you.” He handed Randy a copy of Harry’s ABC of Mixing Cocktails, the recipe tome from the proprietor of the famous Harry’s New York Bar in Paris, reprinted in Great Britain that year. There on the endpaper, in graphite pencil, was the inscription, “TO RANDY FOR THE BEST BARTENDER IN N.Y.,” and then, “HARRY’S IS THE BEST BAR IN PARIS, MAYBE IN THE WHOLE FREE WORLD.”

There are six pages of Jean-Michel’s drawings, carefully rendered on blank-back pages. After four decades, except for the handful of people who may have seen it when it wasn’t in a safe deposit box or, later, Randy’s sock drawer, the work is entirely new to the world. “He just handed me the book. He didn’t go, ‘Oh, there are some pictures in it that I drew.’ It was only later when I looked at it, and thought, ‘Man, this is incredible. He dedicated this to me, and made these great drawings for me.’ He gave it to me with intention. I noticed that he made the drawings on pages that had no printing on the back. It made a big impression on me.”

This is what Randy told the art historian David Ebony after coming forward with the book not all that long ago. I heard about it from Janis Cecil, the art dealer, who told me about the online exhibition she set up so people can see the drawings for themselves. When I called her from L.A., she said, “We know Jean-Michel traveled in 1986,” (to his exhibition at Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles, to Atlanta, to Africa’s Ivory Coast with his girlfriend Jennifer Goode and her brother, Eric; then known as founder of the nightclub, Area; now, interestingly, as a producer of Tiger King.) “But not to Paris. The Barbican materials from the retrospective [Boom For Real, 2017-2018] spell out the chronology of those years. So we don’t know exactly where the book is from, or when he picked it up. Did he find it at some airport kiosk? We don’t know.”

Her point is that even though Jean-Michel was familiar with Harry’s and thought it was the best bar in Paris, (and maybe the whole free world), it’s unlikely that’s where he picked up his copy of Harry’s ABCs. His attachment to The Jones is unremarkable enough. He lived across the street in the studio and apartment arranged for him by Andy Warhol. He ordered takeout regularly, it was his neighborhood joint in his home city. I wonder what it was that drew him with equal strength to the Parisian watering hole with New York in its name.

***

Unlike the unrelated, equally notorious, Cipriani-owned Harry’s Bar in Venice (where I have been), Harry’s New York Bar in Paris (where I have not), is a bastion of American culture. It even opened on Thanksgiving Day, in 1911, careening through World World I in a fog of absinthe and gin, and cementing its status as a refuge for expats who fled to Europe with the U.S. Prohibition hot on their heels.

The proprietors wanted to create a familiar place for the hard drinking, hard thinking creatives and their ilk who were pouring into Paris from the States postwar; the likes of Upton Sinclair, Gertrude Stein and Humphrey Bogart. They wanted somewhere that these people, who likely considered the city’s standbys of champagne and vermouth a pregame, could find a solid boozy cocktail. The original owner, a disgraced champion horse jockey, had a restaurant from Third Avenue in Manhattan dismantled, and shipped the brass rails and mahogany wood bar overseas to recreate his own dive in the 2nd Arrondissement, later selling it to Harry MacElhone. It became the place where Yale and Princeton pinnies draped the walls, the only establishment in Paris where you could find a genuine hot dog. It’s where George Gershwin penned his tune “An American in Paris,” and F. Scott Fitzgerald first nursed a hangover with the newly invented Bloody Mary; where Hemingway supposedly cuffed a live lion onto the street outside, and an annual, (very serious), United States Presidential Election straw vote is ongoing to this day.

In the U.S. of the 1980’s, in another cramped-ish bar on one of the less traversed blocks downtown, on Great Jones Street off Bowery and Bond, a new school of creative punks similarly sought refuge. Its vaguely Southern spirit, homey and comfortable, wove menu items like blackened cornmeal catfish and hambone gumbo with Burger, Bacon Burger, Cheeseburger, Bacon Cheeseburger and Chili Burger. “I think it was a place Jean-Michel could just be, a comfort zone where he was always welcome,”Janis Cecil, the art dealer, tells me.

Jean-Michel was not from the South, and he lived in one of the most metropolitan cities in the world, but it may not have made much difference to him. New York could, and can, be a dark place. “His work,”Janis reminds me, “tells a story of racism.”Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart), painted directly on the wall of Keith Haring’s apartment in 1983, regards the murder by NYC transit cops that same year of another young Black graffiti artist, model and musician in Jean-Michel’s circle. Stewart was dating Jean-Michel’s ex-girlfriend when he died, the artist Suzanne Mallouk, and everyone knew he felt it could just as easily have been him in Stewart’s place.

George Condo, who was coming up around the same time, has said he remembers being turned away from a restaurant in L.A. with Jean-Michel, “his kind” not being allowed. Friends recall he would leave his own gallery openings or a fancy dinner and be unable to have a cab stop and pick him up. Great Jones Cafe was at least one place where being an older, white man wasn’t necessarily an asset, where there was always a familiar face and a cold drink. Perhaps at Harry’s in Paris, Jean-Michel could enjoy all the trappings of American legacy we can claim to love, without the burden of being…in America.

***

Great Jones Cafe is still there, although it’s not Great Jones Cafe anymore. It changed hands a few years ago, was dubbed The Jones in homage to the local nickname, until the new owner realized he was unintentionally confusing people, shuttered it during the pandemic, and reopened last spring under the new moniker, Jolene. While home in New York this fall, I asked one of my best friends to take me for a drink. She’s an artist agent, a gallerist, and I knew if anyone would appreciate what I was looking for, she would. Plus, she’s been to Harry’s and I needed the comparison.

Despite walking down this block dozens of times on my way to somewhere or other over the years, I’ve never stopped here. The year-round Christmas lights and old jukebox, which I’m told was all-star, (hence the Dolly Parton reference) are no longer there, but the fluorescent blue EAT sign still glows from one of the manifold peekaboo windows. The Mardi Gras bead-bedecked bust of Elvis still proudly surveys the damage of the patrons just as he has for over thirty five years. (A few weeks after my visit, in a weird stunt that seems more likely to take place in the old days of post-war Paris, Elvis would be stolen right out of his window by some creeps, and a few days later, by sheer force of community pressure, returned safely to his post.) People who have been coming here that long will tell me it’s a very different place than it used to be, but at the moment, I don’t care. I am not here for a burger. I realize the owner is Gabriel Stuhlman, who ran Fedora on West 4th Street until it closed last year, and still has Joseph Leonard in Greenwich Village, where the salted caramel pudding comes in a jelly jar and is worth giving up a lot of things. I have spent many nights rolling, rosy and content, out of both of those places, and that, really, is why I have come.

***

“He would disappear for a while. He would talk about going away on trips—to Europe for one of his art shows or travelling to Hawaii, places to dry out. I know he’d go to some warm place, and he’d come back looking halfway healthy and off drugs. He’d probably go and score later that day.”

Randy Gun remembers what it was like for Jean-Michele in the last couple of years he was around, when anyone who knew him recognized he was at his worst. Randy himself was working to get clean. Mutual friends were trying to move on, into a new era.

“I’d mention to him, ‘You know what, Jean-Michel, you don’t have to live this way.’ His response was, ‘Well that works for them, but not for me.’ That he came back to visit at the bar after I encouraged him to stop drugging is a testament to his being open to the possibility of change at that time. I know when I was using I was in no mood for listening to anybody who wasn’t drinking or drugging. So really it was a surprise that he would return to visit.”

It was one of the times he came to the bar after that when Jean-Michel brought Randy his book. It is a precious snippet of something personal and private, filled with cultural references to his friend and fellow musician. From an artist whose body of work spanned about seven years, from whom we think we’ve seen everything and know everything there is to know, it is a remarkable gift, given to someone in acknowledgement of whatever sense of comfort and security he’d been able to provide.

***

At Jolene, we eat anchovies in oil, arancini, and roasted carrots. There is good wine and martinis ordered. None of it has anything at all to do with Cajun Creole, but that’s ok. The trashcan in the tiny, grotty bathroom has an “EGO” sticker stuck on the lid. It looks like someone’s small piece of street art left behind.

There’s something here that I’ve been missing for awhile. The ceilings are very low, and the place doesn’t hold more than fifty people, tops. It reminds me of a different time, when I was a little softer, a little sicker, a little more tired. I had my neighborhood place and the biggest luxury, born of familiarity, was not having to open my mouth to order when I walked in, which wasn’t always a good thing. I used to call ahead sometimes from down the block so my drink would be waiting for me. I don’t miss days like that, so long in my rearview. I do miss the comfort of having someone at arm’s length, someone used to observing moral imperfections without assessing them, a port in a storm.

I ask my friend if the space at Great Jones Cafe/The Jones/Jolene reminds her at all of Harry’s New York Bar in Paris. Not really, she says. She remembers Harry’s as being more like McSorley’s on East 7th Street. (The oldest Irish bar in New York, opened in the middle of the 19th century. It did not allow women until it was forced by law a century later, in 1970. Ah, American tradition.) Whatever it is the two bars have in common, it must be something else.

-

The book images and complete interview between Randy Gun and David Ebony is available for viewing in the online exhibition curated by Janis Cecil. A Gift From Basquiat.

Thanks to Richard Crouse and the Last Call podcast for the majority of background on Harry's New York Bar in Paris.

Janet Mercel is a design, food, and features writer from New York currently based in Los Angeles. You can find her on Instagram posting mostly about those things @starwix.

SIMILAR ARTICLES